Can Psychedelics Cure?

Season 49 Episode 15 | 53m 47sVideo has Audio Description

Psychedelics are unlocking new ways to treat conditions like addiction and depression.

Hallucinogenic drugs—popularly called psychedelics—have been used by human societies for thousands of years. Today, scientists are taking a second look at many of these mind-altering substances – both natural and synthetic – and discovering that they can have profoundly positive clinical impacts, helping patients struggling with a range of afflictions from addiction to depression and PTSD.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

National Corporate funding for NOVA is provided by Brilliant.org. Major funding for NOVA is provided by the NOVA Science Trust, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting , and PBS viewers.

Can Psychedelics Cure?

Season 49 Episode 15 | 53m 47sVideo has Audio Description

Hallucinogenic drugs—popularly called psychedelics—have been used by human societies for thousands of years. Today, scientists are taking a second look at many of these mind-altering substances – both natural and synthetic – and discovering that they can have profoundly positive clinical impacts, helping patients struggling with a range of afflictions from addiction to depression and PTSD.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch NOVA

NOVA is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

NOVA Labs

NOVA Labs is a free digital platform that engages teens and lifelong learners in games and interactives that foster authentic scientific exploration. Participants take part in real-world investigations by visualizing, analyzing, and playing with the same data that scientists use.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ADRIAN PRIMEAUX: To me, peyote is a very intimate medicinal herb.

ALBERT GARCIA-ROMEU: Psychedelic-assisted treatments allow us to reinvent ourselves.

YASMIN HURD: They're allowing the brain to see itself.

NARRATOR: In the 1960s, psychedelic drugs were famous for their mind-bending recreational effects, but today, they might offer hope for treating devastating conditions from addiction, to PTSD, to depression.

LEN CAMPBELL: I didn't take psilocybin to go find Martians.

I needed to work with scientists to be able to stop smoking cigarettes.

And it worked.

EVAN CRAIG: I was on antidepressants for about four years prior.

And I haven't been on any since.

(laughs) I haven't felt sadness.

NARRATOR: How is this possible?

Scientists are searching for answers within the brain, where psychedelics alter consciousness and can open the mind to positive change.

It's like reprogramming the operating system of a computer.

You're getting down to very basic, code-level changes.

FRED BARRETT: We observe a radical change in the way that brain regions talk to each other.

BILL RICHARDS: It's not only that these states of consciousness are beautiful and inspiring.

They seem to have therapeutic power.

KATHLEEN KRAL: The psilocybin shifted my perception from negativity to positivity.

NARRATOR: The research is cutting-edge, but early results from clinical trials offer hope.

SCOTT OSTROM: You don't forget the breakthrough moments that you had, and you don't forget what you learned.

They stay a part of you.

JON KOSTAS: I haven't drank since my very first session.

It worked almost like an antibiotic, where I did this treatment and then I was done.

NARRATOR: "Can Psychedelics Cure?"

Right now, on "NOVA."

♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ NARRATOR: Psychedelics: LSD, magic mushrooms, peyote.

These powerful, mind-expanding substances fueled the '60s counter-culture.

For some, they're powerfully transformative-- even spiritual.

CAMPBELL: It was a spiritual experience that I'd never had in my life.

It has probably changed me forever.

NARRATOR: But for others, terrifying and dangerous.

MARCELA OT'ALORA G.: They felt that I was having a psychotic episode.

I was hospitalized.

NARRATOR: And ultimately, they were criminalized.

RICHARD NIXON: We must wage total war against public enemy number one, the problem of dangerous drugs.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: But today, a growing number of clinicians argue that there's another side to psychedelics.

MANISH AGRAWAL: The psilocybin therapy has been the most powerful tool I've seen.

I said, "Wow.

"I feel like I've been treating trauma with stone tools, and there's the state-of-the-art treatment."

NARRATOR: That they have the potential to heal the mind as a treatment for addiction, depression, and PTSD.

ROBIN CARHART-HARRIS: They have this big effect, opening the mind and the brain up for change.

The good that can come out of the responsible use of these substances is quite amazing, really.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: It's an about-face that few saw coming.

RACHEL YEHUDA: How do you shift from a position of, "These drugs are illegal, these drugs are bad for you," to, "These drugs are therapeutic, "this is the way that you heal from mental illness"?

NARRATOR: What are these drugs doing to patients' minds to give some doctors such hope for their potential?

♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ KOSTAS: I grew up in New York City.

It was fairly easy to, to get access to alcohol, through friends, we'd go to a corner deli.

And that all started probably around 12, 13 years old.

It would take a couple of drinks to feel anything or feel good.

But then, a couple of years later, those two drinks wouldn't cut it, or three drinks wouldn't cut it, and I'd need more to get to where I was before, when I first started drinking.

I wouldn't drink every night.

I was more of a binge drinker, so I'd pick my battles.

But during one of those nights, it would be about 23 drinks in a night.

NARRATOR: Over the years, Jon Kostas struggled to quit.

KOSTAS: I went to my first AA meeting at 16.

I tried AA for years.

I tried rehab.

I tried different pharmaceutical drugs.

I've been practicing psychiatry for 21 years, focusing on addiction.

And Jon came to me in his early 20s, and he probably was the worst case of alcohol use disorder I'd ever seen for someone his age.

He'd go on these terrible benders that he was starting to experience alcohol withdrawal, which is very rare for somebody in their early 20s, and I was very scared that he was going to have a premature death because of how much he was drinking.

NARRATOR: Worried that Jon was at risk of death, psychiatrist Stephen Ross helped him enroll in a clinical trial at N.Y.U.

with his colleague psychiatrist Michael Bogenschutz, who was testing a controversial experimental treatment for alcohol use disorder using psychedelics.

During a series of carefully designed therapy sessions over 12 weeks, Jon received two doses of a hallucinogenic drug.

His addiction to a recreational drug would be treated with what most people think of as another recreational drug, psilocybin, which is classified as a schedule one narcotic, right alongside heroin.

♪ ♪ Psilocybin is the mind-altering molecule found in magic mushrooms.

They were introduced to American popular culture in 1957 by a Wall Street banker named R. Gordon Wasson, who wrote about them in an article for "Life" magazine.

These fungi have been used by Indigenous peoples in the Americas for thousands of years.

Psilocybin is just one of a family of substances often called psychedelics.

They include mescaline, found in the North American cactus peyote, as well as synthetic chemicals like LSD and MDMA.

Users report that these drugs bring about an altered state of consciousness, sometimes accompanied by hallucinations or heightened sensitivity to colors, sounds, and patterns.

BARRETT: The entire range of possible visual experiences can be encountered.

Walls breathing, illusory movement-- seeing movement in a carpet when the carpet's not really moving.

NARRATOR: Many also report a loss of ego accompanied by profound feelings of empathy and connection to others, even the entire universe.

And what's perhaps most unusual about these drugs is that after the experience of the so-called trip, users often feel changed in positive ways.

Though there are clear differences between psychedelics, they all, with the exception of MDMA, act in a similar way in the brain.

Each of the active molecules fits like a key into a lock by binding to a specific protein in the nerve cells of the human brain called the serotonin 2a receptor, and this can alter perceptions and even consciousness itself.

And that's central for producing their subjective states, including mystical states of consciousness and these unusual states of mind.

NARRATOR: The drugs are very powerful.

And for some people, the experience of going on a consciousness-altering trip that they can't control or stop can be very challenging or frightening.

KOSTAS: I was afraid of psychedelics.

I never experimented with them growing up because I was too afraid.

I heard all the bad stories of having a bad trip, or I thought I could go permanently crazy.

Or if you stare at the sun, you'll go blind.

And so, when I raised those concerns with the doctors at N.Y.U., they said, "Listen, that's totally normal going into it, "but this is incredibly safe to do.

"We've already properly screened you, "and you're mentally and physically fit to go through this."

NARRATOR: Patients with a personal or family history of psychiatric disorders like schizophrenia, bipolar, or psychotic disorders are deemed to be too at risk for the treatment.

BOGENSCHUTZ: There's a possibility that classic psychedelics could precipitate a psychotic episode or a psychotic disorder in someone who was predisposed.

And that hasn't happened in any of the trials to date, but it, uh, you know, it remains a concern.

Would you like to state your intention for... NARRATOR: In trials like this one, the drug is part of a larger plan to help participants address specific issues, and each psychedelic trip is facilitated by a therapist.

When Jon took his first psilocybin trip in an effort to curb his cravings for alcohol, the experience was powerful.

KOSTAS: There were a few monumental experiences that I saw during this.

(bird calling in distance) There was a glass bottle, a liquor bottle, in the middle of the desert, and all of a sudden, the glass disintegrated into the sand, back into the desert, and just vanished.

And I thought that was pretty powerful symbolism that my addiction was leaving me.

And pretty much after that, I had felt this is going to work.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: Jon stopped drinking after his first dosing session.

KOSTAS: It worked almost like an antibiotic, where I was sick, I had a disease, I went in, saw the doctors, did this treatment, and then I was done.

I don't have to see doctors.

I'm not on any, uh, prescriptions.

I don't go to any support groups.

I live without the addiction, which I never thought would be possible.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: The N.Y.U.

study recruited 93 patients who were randomly assigned psilocybin or a placebo.

All the participants received psychotherapy over the 12-week treatment period.

Jon's case is particularly dramatic.

But the results overall have been encouraging.

ROSS: The psilocybin plus psychotherapy group had a 50% reduction in drinking compared to just the group that got psychotherapy alone.

BOGENSCHUTZ: It's a large difference, it's a clinically meaningful difference, and if these effects sizes hold up, it's a much larger effect than we've seen in any of the medications that are currently approved for alcohol use disorder.

NARRATOR: Doctors are trying to understand why psychedelic-assisted therapy might be more effective than currently available treatments.

They think that the key difference may be in the way that psychedelics can allow the brain to change, rather than simply suppressing symptoms such as craving.

♪ ♪ Our brains are composed of billions of nerve cells that branch out like trees.

They carry messages between each other and connect different regions, which are like departments with different functions.

Such as the amygdala, the department where the emotions associated with memories are stored.

The striatum, the office of reward and habitual behavior.

And at the highest level, the prefrontal cortex, like a front office overseeing them all and making decisions.

So, in the normal brain, you can say especially in, in adults, the prefrontal cortex has this top-down control.

We control our emotions, we control, you know, our, our habits, through very strong prefrontal cortical activity.

NARRATOR: Yasmin Hurd is a neuroscientist who studies the effects of drugs on the brain.

She's found that alcohol can erode the nerve cells that connect departments.

HURD: With alcohol, these branches retract.

They shrink.

And that then diminishes communication between the brain regions.

So, the amygdala is much more hypersensitive to context associated with the, the drug, such as alcohol.

It's, like, acting on its own.

NARRATOR: If the amygdala goes rogue, the result can be irresistible cravings leading to decisions that put alcohol ahead of everything else, even ignoring pleas from the front office to stop.

Habitual behavior takes over.

They stop thinking about what may be the bad outcome.

So their executive control is diminished.

NARRATOR: But when Jon took psilocybin, he seemed to get control over his cravings.

Somehow, the front office re-established its authority.

The research is still early, but scientists do know that psychedelics activate specific serotonin receptors in the brain involved in mood and unusual states of consciousness.

One idea is that activating these receptors may also lead to new nerve cell connections-- even growth.

Perhaps that is the key.

HURD: It's hypothesized that psychedelics will restore the branches in these trees that we know are impacted by alcohol use disorder.

So, by restoring and allowing the branches to grow again, that improves communication once again in the brain.

NARRATOR: But stimulating serotonin receptors or expanding nerve cell connections can't be the full explanation.

After all, the drug cocaine also increases nerve cell connections.

But there may be a critical difference.

HURD: Cocaine will also increase the projections, these branches, but it's too many.

One thing about how psychedelics are used as compared to cocaine, is that cocaine, it's habitual behavior.

They're using it chronically.

It can produce perhaps too much growth.

So, with psychedelics, it seems that the growth may be, you know, it's not too much, it's not too little-- it's just right.

Like the Goldilocks effect, in a way.

NARRATOR: One factor that Jon attributes his sobriety to is the mystical experience he went through, which is often a hallmark of a psychedelic journey.

KOSTAS: Something definitely happened, because my relationship with alcohol changed.

And I don't think about it and have the same emotions I used to have towards alcohol.

ROLAND GRIFFITHS: People ended up having experiences that they rated as among the most personally meaningful and spiritually significant experiences of their entire lifetimes.

And I think that's a really important element that kind of stamps in the enduring attributions made to these experiences.

Because they're profound experiences felt to be precious, felt to be absolutely true.

And that accounts for why, months, years later, people are often reflecting back on that experience and can tap in and draw from it.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: The idea that one or two doses of a mind-altering drug could create such a profound impact with potentially beneficial results is not new.

Western medical research into psychedelics began in the 1940s, not long after the accidental discovery of lysergic acid diethylamide, or LSD.

In 1943, Swiss chemist Albert Hofmann was working with ergot, a potentially poisonous fungus sometimes found on wheat, oats, and rye, which had been used for medicinal purposes for centuries.

Ergot poisoning was known to constrict blood vessels.

Hofmann was hoping to isolate a chemical compound that would reduce the risk of fatal bleeding in childbirth.

In the process, he accidentally absorbed a miniscule amount of LSD, possibly through his fingertips, ultimately launching him on what some would call the world's first acid trip.

"Kaleidoscopic, fantastic images surged in on me, "alternating, variegated, opening "and then closing themselves in circles and spirals, "exploding in colored fountains, rearranging and hybridizing themselves in a constant flux."

Word got out about this mind-expanding substance, and the lab began synthesizing and shipping samples to research centers around the world.

Initially, scientists thought psychedelics like LSD could be used to explore schizophrenia, since a person's tripping experience mimicked some aspects of psychosis.

But then they observed that some patients, including those with alcohol use disorder, reported feelings of transcendence or spiritual epiphanies that helped them to quit drinking.

I was so curious that the most studied indication was the use of LSD to treat alcoholism.

It turns out there was this huge body of research from the 1940s to the 1970s.

And it was a big part of psychiatry.

There were 40,000 participants treated.

It was hailed as a wonder drug.

NARRATOR: But as scientific research continued, some efforts took a dark turn.

The C.I.A.

attempted to weaponize LSD with top secret projects like MKUltra, in which they experimented on volunteers and unsuspecting government employees to see if minds could be controlled, memories erased, people programmed.

And then LSD escaped the lab.

♪ ♪ Ken Kesey, the author of "One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest," was one of the C.I.A.

research volunteers.

RICK DOBLIN: Ken Kesey first got exposed to LSD in a C.I.A.

experiment.

And then later, he became one of the leaders of the hippies.

You know, he helped the Grateful Dead, began at the Acid Tests, the Merry Pranksters.

So, the history of the C.I.A., and the mind control, and the nefarious uses of psychedelics, are interwoven into the cultural story of psychedelics.

Uh, the first experience I had was with seven little mushrooms in Mexico.

NARRATOR: In 1966, the former Harvard psychology professor Timothy Leary promoted psychedelic drugs as a means of personal and cultural transformation, urging youth to...

Turn on, tune in, drop out.

(crowd cheers and applauds) ROSS: Timothy Leary became the pied piper of psychedelics.

And it so alarmed the Nixon government at the time, Nixon declared Timothy Leary the most dangerous man in America, declared war on drugs.

America's public enemy number one is drug abuse.

And enacted the Controlled Substance Act in 1970, which kind of erased them from the history books.

NARRATOR: The act classified drugs like heroin, cannabis, and psychedelics as having the highest potential for addiction and abuse.

ROSS: The whole war on drugs wasn't really a war against, like, stopping people from using drugs.

If you declare war on drugs, you should declare war on alcohol and tobacco, the most damaging ones.

They were absented from the Controlled Substance Act.

He went after psychedelics, which are really not addictive at all.

NARRATOR: The latest revelations about the benefits aren't surprising to many Indigenous populations, who have venerated plant-based psychedelics for thousands of years.

In many cultures, psychedelics have been used in rites of passage and to gain wisdom-- usually administered in specific religious and healing ceremonies.

In North America, some Indigenous peoples use peyote, a cactus that grows in Northern Mexico and a small region of South Texas.

PRIMEAUX: I am Adrian Primeaux.

I come from five generations of peyote people, myself being the sixth and then my son being the seventh generation.

(speaking Native language): (in English): To me, peyote is a very intimate medicinal herb.

We use it as a guide, we use it as a means to synchronize with the universe.

My grandparents explained to me at a very young age that we could acquire any means of success through medicine and peyote if we approached it with the right intent.

NARRATOR: Peyote use can touch on many aspects of life.

PRIMEAUX: How this medicine is able to heal, there's a lot of complex facets.

Within Indigenous forms of thought, we believe that, like, the spirit exists somewhere back there in the subconscious, it's connected to the universe.

So, this plant medicines helps you reach those depths of your ability to manifest whatever it is you can picture in your mind.

Maybe you're picturing pain going away.

Maybe you're picturing your cancer going away.

Maybe you're picturing your body being healthy.

Maybe you're picturing education.

Whatever it is that you're picturing, your subconscious brain has that power to create that for you.

And this medicine is just a tool to help you to reach that point.

(chanting in Native language) HURD: When we think about how Native people have used these substances, it was a ritual.

So there's something still really important about the setting, the ritualistic aspect.

That you can see this positive outcome, you can hear the positivity around you.

All of that then gets encoded into the brain in a manner that, when you're not in that hallucinogenic state, it still stays with you.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: A peyote cactus can take over ten years to reach maturity.

Since the arrival of Europeans, Native American tribes have often been persecuted for peyote use and had limited access to the plant.

Now commercial interests and poachers are putting pressure on peyote's fragile ecosystem.

♪ ♪ Recently, a philanthropist purchased 605 acres of peyote land here in South Texas to provide access for members of the Native American Church, which teaches Native American traditions, sometimes elements of Christianity, and regards peyote as a sacrament.

STEVEN BENALLY: In order to assure that this medicine is going to be available, we have to have some kind of direct connection with this land.

And this land, I think, is an answer to a prayer from years ago that there will be medicine for our children.

♪ ♪ SANDOR IRON ROPE: This land now means the world to all of us.

Mother Earth and what she has provided us.

This represents the future.

It's about what you are gonna teach your children, your grandchildren, and what you're gonna leave behind.

The essence of, of generational responsibilities, you know.

Words cannot suffice what the spirit feels in connecting with this land.

NARRATOR: Psychedelic-assisted therapy is still in its early stages, but scientists are inspired by Indigenous practitioners' careful and non-recreational use of these powerful substances.

One concept that the emerging use in therapy shares with Indigenous practices is the importance of taking these psychoactive substances only in the right environment and frame of mind.

YEHUDA: We know that like any drug, including aspirin, that is in our medicine cabinet, the use of any drug not in the way it was designed to be used can be harmful and even catastrophic.

So when we talk about psychedelics, the setting is very important.

Not just the preparation, not just the integration, but your safety.

Who you're with, what your intention is, what is the physical environment.

NARRATOR: The setting plays a crucial role in a psychedelic-assisted therapy experience.

No detail is overlooked in this physical space, and the mindset, or intention, a person brings to the session is of paramount importance, just as it is when Indigenous people prepare for the use of peyote.

CRAIG: My intentions were just to go in with an open mind.

Whether it be a good trip or a bad trip, just experience it.

My intention was self-exploration, self-understanding, and openness.

KRAL: My intention was to see the face of God.

ERIC GOSS: My intention was to take my experience of having cancer at age 11 and transform it into something neutral, or even something positive.

My intention was to have no intentions.

I wanted to be open to accepting whatever the experience would give to me.

NARRATOR: What draws these patients together is a common enemy: cancer.

AGRAWAL: I've had the privilege of being with you guys all this last year.

NARRATOR: Here in Rockville, Maryland, oncologist Manish Agrawal is the first doctor in the country to run a psychedelic-assisted clinical trial treating depression and other mental health impacts of cancer with group therapy.

CRAIG: I was having really bad monthly depressive episodes where I would just cry all day.

NARRATOR: As many as a third of patients with a cancer diagnosis will experience major depressive disorder.

But perhaps because it exists in the shadow of a cancer diagnosis, the condition is rarely acknowledged.

AGRAWAL: I've been an oncologist for almost 20 years.

And I've been taking care of patients and there's an aspect of that care that was really missing.

You know, we take care of the physical aspects, but then I close the door, and I know so many, um, important issues are really unaddressed.

WOMAN: I wanted to start with something to help us center.

Just like to invite you to close your eyes.

AGRAWAL: I think healing is bringing the body, the mind, the emotion, the spirit back home, to where you feel comfortable with it again.

And so, you can't just fix the physical pain, and then people are healed.

It doesn't work that way.

NARRATOR: Building on pioneering clinical trials at N.Y.U., U.C.L.A., and Johns Hopkins, Manish saw that it was important to treat the depression as part of treating the cancer.

AGRAWAL: That sort of whole-person care.

And that in order to take care of someone, in order for them to feel good, it's not just killing the cancer.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: Manish was surprised by the results.

AGRAWAL: To be honest with you, the numbers were so good that I wouldn't believe it if I wasn't with every session.

I saw every person go through here.

We treated 30 people.

And 82% had more than a 50% reduction in their depression symptoms.

When we measured quality of life, we measured anxiety, all of those were improved.

CRAIG: The experience just kind of made me more aware of myself, and the space that I take up in the world, and the energy that I put out into the world, and how that affects people, too.

GOSS: Prior to the dosing, I had this tendency to get caught up in distressing thoughts related to the cancer.

I noticed a subtle shift, in that, while distressing thoughts would still come up, I was able to let them go for the first time ever.

I don't feel the need to follow them.

NARRATOR: While Eric's endless distressing thoughts and Jon Kostas's alcohol use disorder may seem to have nothing in common, some see a possible similarity at work in the brain.

MATTHEW JOHNSON: These different disorders, I've really thought of them all as forms of addiction.

So whether we're talking about depression or what we normally think of as addiction, these are all just forms of being stuck in a suboptimal pattern.

It's being stuck in a narrowed mental repertoire, a narrowed pattern of behaviors.

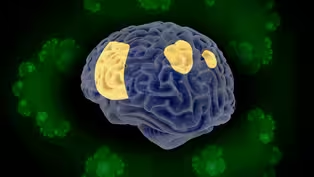

NARRATOR: In patients with depression, scientists have noticed an abnormal increase in activity in a network of different regions in the brain called the default mode network.

JOHNSON: The default mode network refers to this pattern of activity across a number of brain areas that is strongly associated with thinking about oneself, um, thinking about one's past, um, projecting oneself mentally into the future.

NARRATOR: The default mode network activates when a person is introspective, and, under normal circumstances, becomes less active when a person shifts their attention to the outside world.

But brain studies show that under the influence of a psychedelic, the default mode network is quieted, while other regions of the brain increase communication with each other.

A mathematical model captures a normal brain's activity.

In contrast, a brain under the influence of psilocybin reveals a dramatic increase in global communication.

Thousands of new connections form, linking brain regions that don't normally talk to each other.

CARHART-HARRIS: One analogy I've used for how psychedelics work in the brain is the snow globe.

When you pick up a snow globe, you know, the snow's settled at the bottom, it's sort of fixed, and then you pick it up, shake it, and things jiggle around and there's randomness and a kind of chaos, if you want, in the system.

NARRATOR: The user experiences this as an altered and heightened sense of awareness.

But what causes this?

BARRETT: Early in our functional brain imaging studies of psychedelics, scientists were finding that the default mode network was turning down or turning off during these experiences.

And that was a really good place to start.

But we began to then look one layer deeper.

Why was the default mode network turning off?

NARRATOR: New research led neuroscientist Fred Barrett to investigate a region of the brain called the claustrum.

BARRETT: The claustrum is a really thin sheet of gray matter in the brain, tucked deep within each of the hemispheres of the brain.

Recent animal models have shown that it is incredibly highly connected to just about every other region of the brain.

Understanding that the receptors targeted by psychedelic drugs are also really densely expressed in the claustrum, we began to wonder whether the claustrum may be at the center of psychedelic effects.

NARRATOR: Fred believes the claustrum's central location and shape suggest it regulates communication between the departments.

BARRETT: When it's functioning normally, the claustrum is essentially acting like a switchboard.

It's trying to help other brain regions figure out when to turn on and when to turn off.

But when we experience a psychedelic drug, we believe that it's binding to specific receptors in the claustrum and somehow disrupting or disorganizing the claustrum.

It's almost as if the switchboard walks away.

What happens next is that we seem to observe a radical change in the way that brain regions talk to each other.

And it may be within this context that we're experiencing learning and a possible even rewiring of the circuits that govern our behavior.

And it may be that it's that radical reorganization that allows people to encounter new psychological insights that they hadn't encountered before.

NARRATOR: Fred thinks the claustrum's sudden abdication of control may help explain why rigid behavior and thought patterns have a shot at resetting.

JOHNSON: It's almost like they've seen this, like, kind of grand menu within their mind that they weren't aware of.

That this, this greater number of possibilities that they can explore.

GOSS: It took a while to recover.

I was having headaches and muscle pains.

But it was the best headache I'd ever had in my life.

Because it told me that the psilocybin was working.

It was actually physically restructuring my brain, something that I never imagined could happen before.

It's like, uh, reprogramming the operating system of a computer.

You're getting down to very basic, code-level changes that can enduringly change someone going forward.

NARRATOR: As of 2022, there were more than a dozen clinical trials underway involving psilocybin and MDMA.

♪ ♪ Early efforts to revive this research began with individuals like Rick Doblin, who founded the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies, or MAPS, in 1986, to facilitate research into the therapeutic benefits of psychedelics with a focus on MDMA, or ecstasy, for post-traumatic stress disorder.

One of the reasons that MDMA is so successful in therapy is the way in which it builds a certain self-confidence, a self-acceptance.

MDMA can increase the hormone oxytocin, and that oxytocin is really important for bonding.

That may be why that therapeutic bond, the setting that they have, all induce these positive emotional mood states.

DOBLIN: People under the influence of MDMA are able to feel more connected, both to themselves, to their inner world, and also to the people that they're with.

NARRATOR: But these feelings of connectedness and love, paired with an altered mental state, can make participants uniquely vulnerable.

There is concern among researchers about how to ensure patient safety.

And there are not yet universal guidelines or a code of ethics for administering this kind of therapy.

In addition, unlike LSD and psilocybin, MDMA has stimulant properties that can lead to toxic side effects.

MDMA, because it impacts on dopamine or adrenaline, it has a stimulant properties to it, it can induce chills, it can induce nausea, it can increase heart rate, people even thinking that they're having heart attacks.

NARRATOR: Since 2000, more than 200 PTSD patients, including survivors of interpersonal violence, disasters, and combat, have received MDMA-assisted therapy in MAPS clinical trials.

One of those patients is Scott Ostrom.

In 2006, he was deployed to Fallujah, Iraq, where he engaged in multiple combat missions.

OSTROM: Real war is scary.

You play for keeps and everything's unexpected.

You know, you go there highly trained and as physically fit as you can be, but a lot of it's, you know, luck.

NARRATOR: On the front lines, Scott was under constant threat, and would go on to develop PTSD.

ROSS: We know that at its core, PTSD involves the amygdala and overactivation of the amygdala.

The amygdala's the fear center of the brain, and it keeps us alive; it keeps us away from being killed.

But it's the main pathological construct in PTSD.

You have an overactive amygdala.

People respond to neutral stimuli.

Like, a door slamming can remind them of being in combat.

So, innocuous stimuli trigger this exaggerated fear response.

HURD: MDMA seems to calm the amygdala.

By having people not be so hypersensitive to negative emotional state, the prefrontal cortex now can dampen the amygdala, reduce its, its hypersensitivity to distress, to old memories that would cause the amygdala to be overactive.

ROSS: Your prefrontal cortex is really important.

It's the most evolved part of our brain, and it helps you say, "You know what?

The trauma's in the past.

It's not happening now."

And it allows you to rationally think through something and make executive decisions.

People with PTSD, they're just stuck in this, like, fight-or-flight reactive thing.

NARRATOR: Scott qualified for a clinical trial with MDMA-assisted therapy, which helped him to confront traumatic memories.

YEHUDA: If you think of your mind as kind of a hallway where there are a lot of doors, and you try very hard to walk down the hallway and not be triggered by bad stuff that you know is behind those doors.

One of the things that happens with MDMA is, you say, "I wonder what would happen if I opened that door.

Maybe it's not so terrible."

OSTROM: I started seeing this, like, spinning, black, oily ball, and it started off in the distance, and then it would grow, and get closer to me and closer to me.

And then when it would get close enough for me to kind of realize that it was this spinning black ball, I would say, like, "What are you, what are you doing here?"

And it would retreat away.

Instead of asking it what it was, as soon as I surrendered to it, and I surrendered to the feeling that it gave me on the inside and I let that anxiety grow, it started to open up in different layers like an onion.

And when I got to the center, I relived a memory of a phone call that I had with my dad when I was overseas in Iraq.

What I had said to him was, "Dad, I'm really scared.

They said some of us aren't coming home."

And my dad had said to me, "Don't worry, Scott.

"You're highly trained.

"You're with the best guys the Marine Corps has to offer, and don't worry, your training is going to take over."

All of a sudden, I realized that's where this shift happened.

I had become this other person that I needed to become, that I had to become, to survive those combat deployments.

The only thing I could think to name that person was the Bully.

NARRATOR: Taking his father's words to heart, Scott let his training take over to become the Bully.

But the Bully could not shield him from the pain of loss.

One thing that was really tough was not being able to save someone that I felt close to.

The vehicle that he was riding in, um, ran over an anti-tank mine.

(explosion roars) I had ran up to the vehicle shortly after that explosion, and the vehicle had caught fire.

My friend was trying to get out of the passenger seat, and he couldn't, and I couldn't get to the passenger door.

My body wouldn't let me get any closer, because the fire was too hot, and he burned alive.

There was nothing I could do.

NARRATOR: Nightmares of the war followed Scott home, along with painful regret.

OSTROM: I felt a lot of guilt for not being able to save him.

And for a long time, I punished myself for that.

My interpersonal relationships were completely down the tubes.

I had high-risk behaviors like getting into fights, self-medicating with drugs, alcohol, being just aggressive and martial in general.

And after, like, three-and-a-half years of having nightmares every night, I really started to kind of fall apart.

NARRATOR: Scott wasn't alone in his desperation.

Every day, almost 20 military veterans die by suicide.

Current treatments for PTSD are of limited benefit.

After identifying the Bully within him, after the first MDMA dosing session, Scott had another breakthrough in a subsequent session with his therapist, Marcela Ot'alora, and Scott's dog, Tim.

OSTROM: Marcela was sitting in her chair and I was spooning Tim on the rug.

And Marcela had just told me, "Well, would it be okay "if you asked the Bully if Scott can take over for a little while?"

And being in the state that I was in, I was, like, "Hm, I don't know, I guess I'll give it a shot."

So, I had an unconscious conversation with the Bully, where I was able to ask if it was okay if I took over for a little while, Scott took over.

OT'ALORA: Right, and it was more, like, can he step out, to the side for a moment to see who else was there, to see what other parts of Scott are there?

And it was just this beautiful time of being able to connect.

And I think after that, you didn't call him a bully anymore.

NARRATOR: The MDMA helped Scott to reframe the guilt he felt over not being able to save his friend's life.

OSTROM: You don't forget the breakthrough moments that you had, and you don't forget what you learned.

They stay a part of you.

So no, MDMA is not something you microdose, it's not something you have to take all the time.

Um, it's, it's just the key that fits into the psychotherapy lock.

The psychedelic-induced experience can help a person get unstuck in a way that's not just, just being told it, but really experiencing it firsthand, and I think that's where there's a lot of power in these experiences.

NARRATOR: Remarkably, nearly 70% of participants in phase three of the MAPS MDMA-assisted therapy trials no longer qualify for a PTSD diagnosis.

DOBLIN: We learned that MDMA-assisted therapy works in combat-related PTSD.

It works in the hardest cases.

And it works regardless of the cause of PTSD.

So our phase three studies are PTSD from any cause, and if we manage to get FDA approval, it will be for PTSD from any cause.

NARRATOR: Rick Doblin thinks that the treatment could be beneficial to many more people, including some who struggle with stressful experiences that aren't easily associated with PTSD, like bullying and systemic racism.

But introducing psychedelic therapies to communities of color brings a special set of challenges.

MONNICA WILLIAMS: Because this is a new treatment, because it's connected to research, and because it's connected to a substance that's been stigmatized due to being illegal, a lot of people of color are very wary.

The African-American community has suffered a great deal from the war on drugs and having their communities targeted due to drugs.

Just growing up, I was always taught, stay away from drugs.

This is a trap.

This is a way that people are gonna get you and put you behind bars.

NARRATOR: Aware of abuses in the past, MAPS teamed up with therapists from communities of color to offer them training in the use of MDMA-assisted therapy.

One of the participants, Sara Reed, chose to experience an MDMA dosing session as part of her training to become a psychedelic-assisted therapist.

REED: One of my therapists made a comment about, "There's a part of you that doesn't want to be understood."

As a Black woman, there is nothing more that I want than to be understood.

I felt that so deeply in that moment.

Particularly with problems like racism, I mean, one of the ways that it hurts people so much is that you're experiencing it all the time, but other people don't see it.

And even when you point it out, they're, like, "Oh, are you sure that's what happened?"

Or, "That didn't really happen," or, "Maybe you're being too sensitive," so your whole experience is one of being invalidated.

And of being not seen and not heard.

NARRATOR: Learning from this experience, Sara went on to provide one of the first MDMA-assisted therapy sessions for a participant of color experiencing racism and post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD.

(music playing, singing along) ♪ I'm dropping new weights ♪ ♪ Bugs Bunny, feelin' so sunny ♪ NARRATOR: From a young age, Kanu Caplash had been the target of racist remarks and bullying.

WILLIAMS: With racism, often it's not necessarily one big problem.

It's not necessarily, like, oh, the Ku Klux Klan came, and burned a cross on your lawn.

And now you have trauma.

It's usually a lifetime of smaller things that may have some big things here and there, but at some point, the stress becomes overwhelming, and it tips into PTSD.

We call that racial trauma.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: Kanu was already experiencing racism when, as a swimmer, he was sexually assaulted in the locker room, tipping him into PTSD.

CAPLASH: So the nightmares and the symptoms really started to take effect after the sexual assaults, which happened when I was 13.

I was sexually assaulted, uh, four times.

If it wasn't for the study, I don't know if I'd be, you know, alive today.

'Cause, like, there was times kind of right before the study, where I was really, really struggling, where I really wanted to kill myself.

REED: Our site was focused on providing participants with a culturally informed experience with MDMA therapy.

And as one of his therapists who is attuned to his racial background, his religious background, his childhood upbringing, I wanted to incorporate chants.

During one of his dosing sessions where one of those chants played, I just remember it seemed like something really resonated with him in that moment.

♪ ♪ He was actually able to go back to a childhood memory.

CAPLASH: I'd be transported to, like, a different galaxy.

Look down, and I see this long set of piano keys going on to infinity.

And it's crazy, 'cause as I'm going down the keys, I can see different parts of my life.

I find that sexual assault, 'cause I'm, like, that's the big one.

That's the one that I had trouble remembering, and kind of trouble processing.

And I remember, I jumped in and I woke up on another world.

I sat there and I meditated on that planet for, like, a thousand years.

And I was able to go through my memory, and walk through it like a museum.

And, like, walk through each of the incidents and remember vividly everything that happened.

I was, like, flexing my arms really, really hard and just getting out all of the, effectively, like, pain.

You know, that was just kind of stuck in my arms, stuck in my body.

The one thing I learned through the study is, like, there's no other way but through.

The only way to handle the beast is to confront it.

To recognize it is what it is, it's a part of you, um, but it doesn't necessarily have to define you.

And when you do that, eventually, you know, you will accept more of yourself.

But also, you will accept, like, the larger world in a more kind of positive light.

NARRATOR: As of 2022, MDMA-assisted therapy for PTSD is in the final stages of the FDA approval process.

Psilocybin-assisted therapies for major depression and other conditions are also in the FDA pipeline.

While hope runs high for psychedelic medicine, scientists are quick to point out the inherent risks.

WILLIAMS: People think about psychedelic drugs and they think, oh, you know, you're gonna kind of zone off into a world with clouds and unicorns.

But I see them more as medicines, as tools for healing.

And, um, and they are powerful tools.

And so, I think, as such, they require a lot of respect, because I think something that has that kind of power to heal could also cause harm.

You gotta use it safely.

NARRATOR: Scientists are cautiously moving forward.

AGRAWAL: The psilocybin therapy has been most powerful tool I've seen.

It's not for everybody, it's not to be, it's not a magic bullet, but it does change things meaningfully for many patients.

GRIFFITHS: It's so different than any other intervention we have within psychiatry, because it's changing the very narrative structure about how people tell their own story, what they believe going forward.

YEHUDA: We're not going to have this whole jigsaw puzzle completed for a while.

And I think that we want to stay a little humble about that.

The less we kind of interpret, and the more we just state what our observations are, I think the better off we're going to be.

♪ ♪ ANNOUNCER: To order this program on DVD, visit ShopPBS.

Or call 1-800-PLAY-PBS.

Episodes of "NOVA" are available with Passport.

"NOVA" is also available on Amazon Prime Video.

♪ ♪ ♪ ♪

Can Psychedelics Cure? Preview

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: S49 Ep15 | 30s | Psychedelics are unlocking new ways to treat conditions like addiction and depression. (30s)

How Psychedelics Change the Brain

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S49 Ep15 | 4m 11s | Scientists found that psychedelic drugs may change how brain regions talk to each other. (4m 11s)

Psychedelics as Medicine: The History of Peyote

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S49 Ep15 | 4m 2s | Indigenous communities use this small psychedelic cactus as a medicinal herb. (4m 2s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- Science and Nature

Capturing the splendor of the natural world, from the African plains to the Antarctic ice.

Support for PBS provided by:

National Corporate funding for NOVA is provided by Brilliant.org. Major funding for NOVA is provided by the NOVA Science Trust, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting , and PBS viewers.