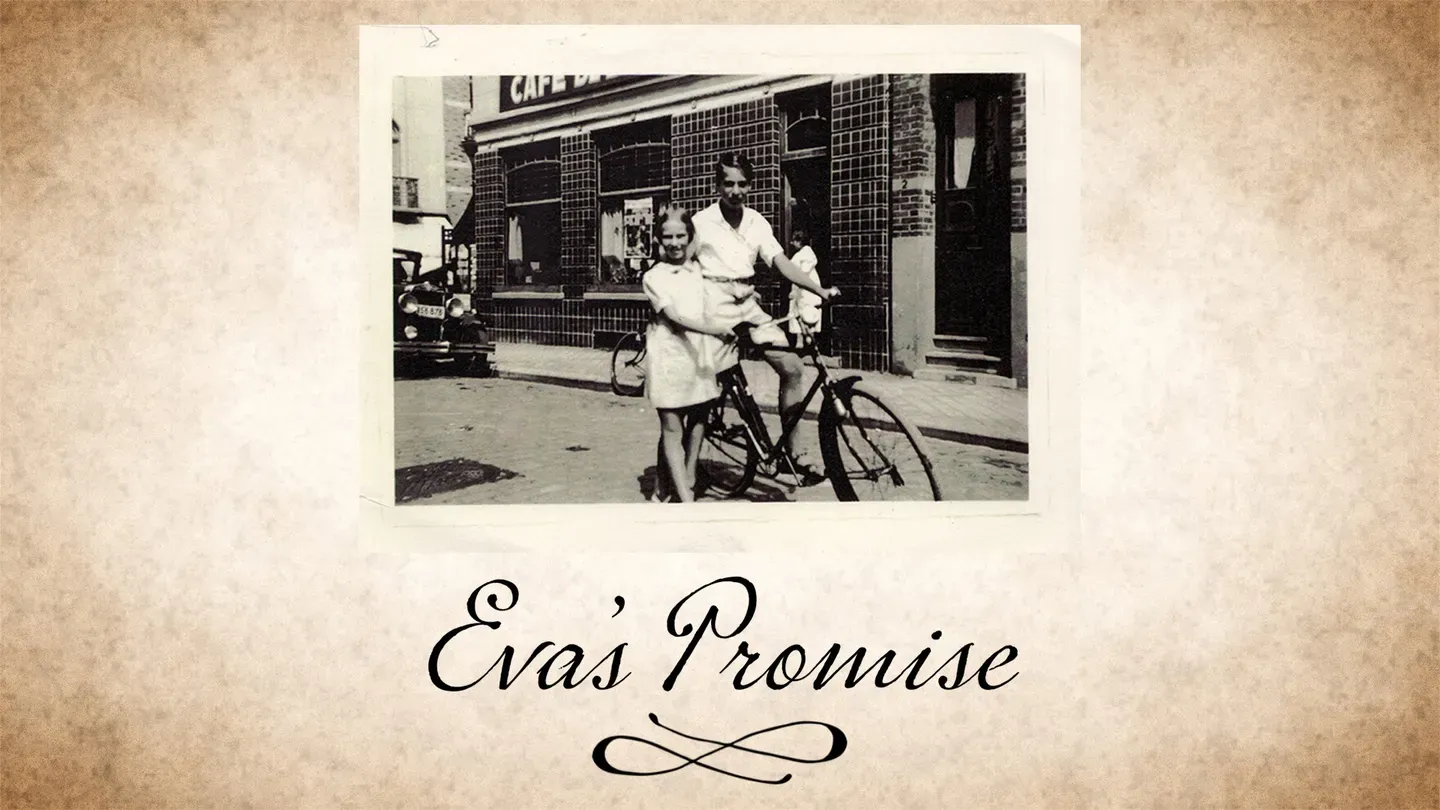

Eva's Promise

Special | 56m 29sVideo has Closed Captions

Anne Frank’s stepsister fulfills her promise to share her brother’s hidden WWII artwork.

On a train to Auschwitz, Eva made a promise to her brother Heinz. If he did not survive, she promised to retrieve the paintings and poetry he hid under the floorboards of his attic hiding place. After the war, Eva’s mother married Anne Frank’s father. While the world knows Anne’s story, this film introduces Heinz, his artistry, and his sister’s efforts to find and share his remarkable legacy.

Eva's Promise is presented by your local public television station.

Distributed nationally by American Public Television

Eva's Promise

Special | 56m 29sVideo has Closed Captions

On a train to Auschwitz, Eva made a promise to her brother Heinz. If he did not survive, she promised to retrieve the paintings and poetry he hid under the floorboards of his attic hiding place. After the war, Eva’s mother married Anne Frank’s father. While the world knows Anne’s story, this film introduces Heinz, his artistry, and his sister’s efforts to find and share his remarkable legacy.

How to Watch Eva's Promise

Eva's Promise is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

[ Soft music plays ] ♪♪ -This is a wedding opposite where we were living.

where Anne Frank is watching.

♪♪ This is Anne Frank looking out of her window because there was a wedding taking place.

♪♪ ♪♪ This is my brother Heinz who was just cycling around, and by chance, somebody filmed it.

Because it was a wedding they were filming but obviously they filmed a little bit more.

I had to look carefully to see if it really was Heinz, but it definitely is Heinz.

♪♪ My mother very often said, "Anne is so well-known.

Wherever we go, people know who she is, but Heinz, who was just as talented, just a wonderful young man, nobody knows about him."

♪♪ My name is Eva Schloss.

[ Indistinct conversation ] ♪♪ ♪♪ I had an older brother named Heinz.

My brother was just 16 and 17 years old when my father encouraged him to spend the time painting.

It's a good thing to do.

And he started to write poetry.

♪♪ ♪♪ This painting is by Heinz.

That's "Time is Running Out."

That's a death mask, and time was running out.

So that's a sad, serious picture.

♪♪ And then there was a knock on the door, and the Nazis storm in -- two Dutch policemen and two Nazis -- and took us away.

There was my father and Heinz and my mother.

♪♪ The train to unknown destination, because they never told us where we were going.

I mean, we were all frightened.

No doubt about that.

But Heinz was really petrified.

And he hardly ever spoke.

He told me that his paintings and his poems are hidden under the floorboard in the house where they were in hiding, with a note on it, "This belongs to Heinz and Erich Geiringer, and after the war, we are going to pick it up again."

"And so, if I don't come back, please go and fetch them."

And I was -- of course, I was too upset.

I said, "Of course you'll come back.

Of course we both will.

We'll all survive."

And so on.

He said, "Yeah, yeah.

Well, I know, but just promise me that if I don't come back, that you will go and get it."

♪♪ ♪♪ -I am Liesbeth van der Horst.

I'm director of the Dutch Resistance Museum.

The museum was set up in 1984 by people of the former resistance.

They thought we should tell the story of the Second World War and the resistance for young people.

-1930.

There is a worldwide economic crisis.

Many people are unemployed and dissatisfied.

♪♪ -We decided to make a children's museum in a new part of the museum.

And there we tell the story of four children -- a Nazi girl, an average boy, a boy whose parents are in the resistance, and a Jewish girl, and that's Eva.

-[ Speaking Dutch ] -You see, democracy is declining all over Europe again and in the world again.

So it's important we tell the story how important it is to be free.

It's important for Eva, and it's important for the Dutch Resistance Museum, as well.

-My name is Nina Siegal.

I'm a New York Times journalist based in Amsterdam.

And I'm the author of "The Diary Keepers."

♪♪ We are living in a time of rising antisemitism.

A lot of people are forgetting these stories.

And it's very important to record these survivors for their experience and also for their personal firsthand narratives, because those are so important to us understanding that this is not a story of numbers.

♪♪ -I'm Susan Kerner.

I'm a theater director.

I've known Eva for more than 25 years.

In the '90s, I directed the first production of the play "And Then They Came for Me: Remembering the World of Anne Frank."

That play has toured all over the world.

Eva has often participated in post-play discussions.

Now Eva wants to tell the story of her brother, Heinz.

Like Anne Frank, he was a remarkable young person who had immense talents and gifts to share with the world.

-People will see who he was.

He will be remembered.

Wherever I speak, this is a very important part of my story now, telling about my wonderful brother, what a wonderful relationship we had, and how talented he was, how he was going to contribute a lot to the world.

♪♪ Well, we had a very, very nice youth in Vienna.

We were all very, very happy.

We had a beautiful home.

-3-year-old Heinz was unprepared to have a baby sister.

He developed a stutter.

His parents took him to see a psychologist, Anna Freud, daughter of Sigmund Freud.

She cured his stutter.

-But when Heinz was 4 years old, his eyes started to get to problems.

And eventually, he lost his sight in one eye.

So that was, of course, a terrible thing for the family.

They were very, very upset, and Heinz was very worried all his life that he might lose his sight of his other eye.

[ Piano plays soft music ] ♪♪ My grandfather was a wonderful pianist.

And Heinz was very interested in the piano.

He started already, when he was 4 years old, to teach him to play piano.

He had a perfect ear like my grandfather.

When he heard something, he could just play it.

He found his notes and could play it.

[ Marching band plays up-tempo music ] My parents knew what was happening in Germany.

-Signposts at city limits bear the legends "Jews not wanted.

Jews keep out."

-Hitler came to power in '33.

Austria was not the same anymore.

It was become -- start a bit dangerous.

There were riots and all kind of things, I didn't really feel insecure or scared of anything.

But Austrian people, certainly adults, would know it was already a very, very difficult time.

-[ Speaking German ] [ Marching band plays up-tempo music ] -In Vienna, city of song and music known 'round the world, 500,000 pack the streets, while buildings are covered with the symbols of the German Reich.

Adolf Hitler, modern Caesar, enters the land of his birth.

-When the Nazis marched in, in March 1938, we had Christian friends.

We were Jewish, but not Orthodox or anything.

My best friend was actually a Catholic girl.

I always went to her home, and we played.

But after the Nazis, the next day already, I didn't realize that things had changed.

I went to my friend, and when the mother saw me, she opened the door and looked at me with such hatred and said, "We never want to see you here again."

And she slammed the door in my face.

[ Soft, dramatic music plays ] ♪♪ My father's clients didn't pay him, and so on.

And so the factory went bankrupt.

And so we moved from the big house to a much smaller apartment.

One day, Heinz came home from school, and he looked terrible.

He was beaten up, his clothes were torn, blood was streaming from his face.

And of course, he was extremely scared that they would have bashed his eye in or something.

It was terrible.

-Jewish shops were looted.

Windows were smashed.

Eva's father, Erich, moved to the south of Holland to find work in the shoe industry and find a place for his family to live safely.

-My father had tried desperately always to get a visa for us to come and live in Holland, as well.

And in February 1940, so during the war already, we got a visa.

So, my father hired a furnished apartment because we had no furniture or anything.

-The Geiringers came to live in the Merwedeplein in Amsterdam.

It was a new-built part of the city.

So a lot of well-to-do Jewish people who fled came to live there.

-Well, in this apartment, it was beautifully furnished, but, as well, there was a wonderful piano.

I think it was even a Steinway piano.

And Heinz was, of course, delighted to play on such a wonderful instrument.

Heinz settled very easily.

There was a lot of music, and he got an accordion, which was very popular.

There was Maurice Chevalier of course... -♪ I don't care what's down below ♪ ♪ Let it rain, let it snow ♪ -...but, as well, Charles Trenet.

And there was a very famous piece of music called "La Mer," "The Sea."

-♪ A des reflets d'argent ♪ ♪ La mer ♪ -And Heinz learned that, of course, immediately on the accordion, and he played.

We were quite popular because Heinz talked with everybody.

[ Indistinct conversations ] [ Accordion plays mid-tempo music ] ♪♪ -Heinz went to the Amsterdam Lyceum, which was a very good school.

And he was a very good pupil.

And Heinz, of course, he had played piano, he got the accordion, then he got a guitar.

And he was sitting on the steps, playing.

So all the other kids who liked music came, and so he had made friends immediately, lots of friends.

He was very, very popular.

-It was a happy time for Eva and Heinz.

They sailed Heinz' small boat on the Amstel River.

They made friends and they met their neighbors in Merwedeplein, including the Frank family.

-One day, a little girl came to me and said, "You are new here."

She said, "Come up to my apartment, then my dad can speak German with you."

So I met her family, and the mother always made lemonade and cookies.

And we became friends, but not best friend.

Anne went to the Montessori school, and I went to the local -- ordinary local school.

-So they were, you could say, neighbors.

Eva knew Anne.

They were -- They had the same age, but Anne Frank was very popular and already interested in boys and so on.

And Eva, she was very childish and shy.

So they were not really friends, but they knew each other.

-One day, Anne said, "Oh, you're so lucky.

You have a brother.

I only have a sister."

So she said, "When can I come and visit you in your apartment?"

And she did come, of course one day, but Heinz wasn't interested.

He didn't want yet a girlfriend, and certainly not the age of his little sister.

♪♪ I started to be quite happy.

But, unfortunately, not very long, because in May, at night, we heard airplanes and guns and all kind of noise.

And the parents put on the radio, and it's a terrible news.

[ Explosions ] [ Dramatic music plays ] ♪♪ -When the sun rose on that fateful day, the Nazis invaded the Netherlands.

Without warning or the slightest provocation, they unleashed upon their innocent neighbor the full terror and fury of a devastating blitzkrieg.

-People became very anxious.

We were stuck.

Nobody was -- could leave anymore.

But nothing happened.

Life carried on like normal.

But then, slowly, after about a couple of months, measures against the Jewish people started to come in newspapers, on the radio, posters.

And it was a nuisance, but it wasn't life-threatening.

For instance, you were not allowed on the tram.

Well, everybody had a bicycle.

You had to stay in after 8:00, and you are not allowed to go out before 6:00 in the morning.

Well, it didn't matter.

Monopoly, the game Monopoly, had just come out.

So, we started to play, in the evening, Monopoly.

-The end of 1940, the Jewish civil servants were dismissed.

Then, all the Jewish people had to register.

And halfway 1941, everybody had to have an identity card.

And for the Jewish people, a "J" was stamped in it.

So, gradually, they were not allowed to go to the market anymore, to the cinema, to the swimming pool.

And then there came separate schools.

So it was all done by very small steps, to prevent people to resist.

-The announcement came at the end of April that all Dutch Jews would have to wear a star sewn into their clothing.

It was distributed by the Jewish Council and with instructions, people had to go home and sew it into their clothes themselves.

I think it was clear to most people that this was a branding, that this was a way of separating the Jews, and people felt very embarrassed that they had to wear them.

[ Soft, dramatic music plays ] ♪♪ -The principal at that time, who was called Gunning -- he started this school, and he was also -- he stood up for the Jewish pupils at his school during the war.

He refused to have people sign [Speaking Dutch].

That's a kind of document that you needed to sign, whether you were or were not Jewish.

He rounded up all his students here in this auditorium, as well, and he gave what is called a 'fare thee well" speech to them.

And he was principal of our school from the beginning, 1917.

He's known for the extent to which he stood up for his Jewish pupils and accepted the consequences that were attached there.

♪♪ -He was in the same class as Margot Frank.

Heinz was very, very good in languages, and Margot was not so good.

And Heinz was not so good in the science, and Margot was, so sometimes they did homework together and helped each other.

And then we got the postcard, ordinary postcard, that Heinz has to come within a week to a certain place to be deported to Germany, to work in a German factory.

And many, many friends of him, including Anne's sister, Margot, got it as well.

And many, many other young people.

I think he was only 15.

So my father called us together in the evening, and he said, "Heinz, you are not going.

We are going to go into hiding."

And my father explained, "I have found some wonderful Dutch people who belong to the resistance."

-I don't think we can talk about "the" Dutch resistance.

There was not one.

There were a lot of small groups and different organizations and individuals who helped Jewish people.

-They arranged all kinds of places in hiding, and they had a network of contacts when an address was not safe anymore.

And they had big organizations for forging papers, among which the identity cards.

You could have a false identity card on another name, a not-Jewish name.

And, yeah, sometimes you could even go on the street with it.

I said, "Hiding -- I don't understand."

So my father explained, "I found some wonderful people who will keep us safe.

But the apartments in Holland are very small.

I couldn't find a family who would take in four people.

So we have to split up."

And I started to cry.

I said, "No, I want to stay together.

I don't want to be separated."

And my father said, "If we are in two different places, the chance that two of us will survive is bigger."

"Survive."

So, I think that was the first time that I realized it is a matter of life and death.

And I must say, from then on, I became really very, very scared.

♪♪ The hiding was not as simple as you might think, because the Nazis did those house searches, and people became scared and couldn't take the tension, because it was always at night, so people didn't dare to sleep.

They really wanted to catch every Jew.

-In the Netherlands, there was a system of Jew hunting that was very active and very aggressive, and people were paid by the head for every Jew that they were able to turn in.

-People were too scared to keep people for a long time.

Sometimes it was six months, but sometimes only several weeks.

So both we changed about six, seven times in the two year, where we were hiding.

♪♪ Last place where Heinz and my father was taken, were not in Amsterdam.

That was outside, in a little town.

Soestdijk, it was called.

Heinz had so many different talents that my father said to Heinz, "You have to be silent, but let's paint."

And at that time, the Dutch used to be painting.

It was a big hobby, so there was enough material to buy.

So the people who -- where they were hiding went out and bought stretchers and linen, and so they had plenty of material like that to start with.

And he started to write poetry, because you can't paint -- especially with his one eye, his eye got tired.

So he was actually very, very occupied.

-There's a term that historians use for what we call Jewish cultural resistance under these circumstances, called "amidah."

And it basically refers to the idea that continuing to practice your cultural traditions, continuing to elevate Jewish culture, to write Yiddish songs, to make paintings, to think about music under such circumstances is a form of spiritual resistance and cultural resistance.

And I think that ties in to what Erich and Heinz were doing.

♪♪ -I'm the grandson of Eva Schloss.

I'm actually a poet myself.

And so, when I read some of his work, I'm just amazed at how mature his perspectives were on life, but also how the situation that he was living in, how dark it was and where his thoughts took him.

You know?

And, yeah, it's really sad.

"When you set out to write a poem, look inside yourself for what are called feelings.

For no matter how little you might know, in your own world, you are the king whose wish reigns supreme, who is all-knowing.

And write about the battle within your soul, about a love effervescent in your heart.

Write also about how you see life.

Write about people who care about you.

Write about what you feel when you see nature.

In the end, nothing can ever emerge as purely.

Nothing can be as simple and yet as beautiful as what is born of your inner self, what is destined for you and you alone, what blows you away like a soft breeze."

When I read his poems, what really comes through is his desire to express himself and to be recognized and to explore life, to share his experiences, his thoughts, to bring into the world so many of his sort of feelings and what was happening within him.

But, you know, obviously being in hiding, his situation and the kind of grave destiny, which he almost anticipated, I think, you know, there's definitely a real heaviness and an anticipation of what was coming.

♪♪ -We had to visit them because I got very, very upset not being with Heinz and my father, not seeing them, and I missed them so much.

Sometimes we had to go by tram, but then, in the last hiding place, we had to go even by train, which was, by itself as well, dangerous.

Very often, we could visit only if there was no room for us to stay the night.

We were only allowed to come for the day.

So my mother and my father usually disappeared pretty quickly.

[ Laughs ] And so I stayed with Heinz, of course.

He told me again and showed me everything what he has done.

He read to me some of his poetry, and he showed me his paintings.

We played chess together.

Yeah, so, we had really a fantastic time.

♪♪ -After two years, the family was running out of money.

Eva's father decided it was time to find a new hiding place for himself and for Heinz.

-Many people had been arrested.

Many people didn't want to do it anymore, and so it was very difficult to find a hiding place.

And so, eventually, somebody said there's a nurse who says she has a safe house, and they could come there.

And so my father phoned and said, "Look, it's so near, it's about 10 minutes walk, Why don't you come and visit?"

And he asked the nurse if it's alright that we can come.

And she said, "Yeah, sure, sure, you can come and visit."

So we were very happy, were very excited, and they were very happy there.

They made a nice meal, so they were extremely happy.

And it was near us.

Everything was good.

And then that was on a Sunday, and on Tuesday was my 15th birthday.

And then there was a knock on the door, and the Nazis storm in -- two Dutch policemen and two Nazis -- and go right for my mother and me and took us away.

♪♪ We got there, and they separated me from my mother and they took me in a tiny little room with a big Hitler picture on the wall and threw me on a chair.

And two Nazis with guns were standing next to me and just started to throw questions at me.

"How long have you been hiding?

Where have you been?"

And this and this and this, and I was in complete shock.

I knew this is probably the end of my life.

♪♪ -The Geiringer family was betrayed by a nurse who was a double agent.

She invited the Nazis in, served them lunch, and then they arrested Heinz and Erich and took them to the police headquarters.

They had followed Eva and her mother home when they visited Erich and Heinz.

And they were arrested on the same day, Eva's 15th birthday.

♪♪ -We traveled for about three hours.

They didn't tell us where we were going.

And we came up to Westerbork, which was a holding camp.

-Westerbork was a transition camp in the eastern part of the Netherlands, and all the Jews were brought there before they were deported to the concentration camps in Eastern Europe.

♪♪ ♪♪ -There's very important footage that was shot on May 19, 1944, by an inmate at the camp, under the direction of the Nazi commander.

And this was definitive evidence of the Holocaust taking place.

And it shows us, in a way that very little footage does, what it was like for people to get on these trains to death camps from the Netherlands.

-It was a cattle car, certainly not even for animals.

It was -- I think it was just for goods.

It was certainly not for human beings.

There was nothing in it.

So, just the floorboard, and too many people were pushed in it.

So, there was no air, nothing.

It was really a terrible, terrible journey.

But the good thing, I always say, that was really the last time that we were together as a family.

So it was terrible, but I know we were still together.

My father apologized to us that from now on, he won't be able to protect us.

And he really cried.

He was very upset.

He said, "I won't have any power to look after you."

Heinz -- he hardly talked.

He was very, very nervous, very upset, very worried, I think.

And he told me that his paintings and his poems are hidden under the floorboard in the house where they were in hiding.

"And, please, Eva, please go and pick it up and show it to the world what I had achieved in my short life."

And I said, "Of course, you'll survive.

If I survive, you survive.

We go together."

He said, "No, no.

But promise me that you will go even if I'm not there."

So, very reluctantly, I promised.

-"Encouragement."

"Behold, the man, a dark silhouette emerging from this heavenly grayness, hunched over, lacking a divine inner spark.

He gazes dull-eyed and, oh, so uninspired, his mouth open in a pointless prayer.

Behold, the man, mocked, trampled on, slain, a bowed back, a limp arm, a blank look, empty and perturbed.

His body already broken.

His spirit, too.

His vigor sapped by sadness.

Is that a man, that pitiful creature?

A man of words, courageous deeds, a warrior tall and proud and brave?

A pillar of the new society, muscular and strong, stubborn and wild?

Come on, hold your head high.

You can do it.

Be a man.

You are young.

You have a whole life ahead of you.

Stand up.

Take pride in yourself."

Do you think that -- I mean, you obviously would've read his poems and looked at his paintings a long time ago.

Do you think that they shaped the way that you see the world, and the way that you thought about your experiences and things?

-Well, his poetry is -- well, some are bit human, full with jokes.

But, in general, they're actually quite sad... -Mm-hmm.

-...and -- but have a meaning.

And it's always that people try to make a good life for themself, but it doesn't end that way.

So a lot of his poetry is very sad-ending.

[ Train chugging ] [ Bell clanging ] Well, after three, four days -- we don't even -- we lost count, really -- the train stopped, and we heard a lot of noise and dogs barking.

And then they opened the door.

And we saw a lot and lots of people.

Some soldiers, S.S., and some inmates in the camp, with striped -- the famous striped uniforms -- pajamas, we call it -- and the hats.

And then there was a big sign, "Auschwitz" -- "Auschwitz" in Polish and in German.

And we realized that we were in Auschwitz, where the gas chambers were.

So we realized that that is probably the end of our lives.

-The family was separated.

Eva and her mother were taken to Birkenau, about 2 miles from Auschwitz, the main camp.

-This was again a very, very terrible moment, because we cling to each other.

So, my mother to Heinz, and me to my father, and to each other, and I cling to Heinz.

And we cried.

And my mother, of course, held Heinz for a long time.

But then, with sticks, they tried to separate us.

And the men walked away.

-And that's when Eva and her mother came face-to-face with the notorious Dr. Mengele.

-He was the camp doctor.

A proper medical doctor.

Meticulously clothed, polished boots, gloves even.

And like a conductor, little stick in his hand.

And he came.

So, that was the first row of five.

And he looked, fraction of a second, decide right or left, decided where to go.

Of course, we had no idea.

When he looked at me, he didn't realize how young I was.

So, I went with my mother to the right side.

♪♪ ♪♪ -Eva and her mother were fortunate to work for a time in a relatively safe place.

It was a place where inmates searched through the belongings of new arrivals at the camp.

It was there that Eva had a chance meeting with her father.

-One day, I was sitting there, eating my bit, what I found of food.

There was plenty of things you found.

And so, on the other side of the fence, a man in a striped uniform, with a striped hat on.

And I looked again, and it was my father.

And I just couldn't believe it.

And I called, "Vati, Vati."

And the man looked around.

And he saw me, of course, [Gasps] and were gaped open.

And of course, that was amazing.

That was amazing.

And he said, "Where's Mutti?"

I said, "Yeah, yeah, she's working here with me, as well.

And Heinz?"

"He's okay," he said.

He didn't say what he was doing.

"He's okay."

And then he said to me, "Can you get cigarettes?"

So, I said, "But you never smoked."

So, he said, "Yeah, but it is a good way of -- you can exchange it for anything, cigarettes."

So, of course, you could find anything.

So, he said, "I'll come next day again and see if you can have the cigarette."

And I found whole boxes of cigarettes.

And I threw it over the fence when the S.S. wasn't looking.

So, I was able to do this a few days.

And then I didn't see him.

Auschwitz was the only camp where they tattooed people.

It's very, very faded in a way.

It was much stronger -- A-52-72.

♪♪ -The most horrific time for Eva came when her mother was "selected," and Eva thought she had perished.

A cousin who was working as Mengele's nurse saved Fritzi's life and brought the mother and daughter back together again.

When the Nazis retreated, in January 1945, Eva and her mother were in the infirmary.

Fritzi was near death.

The Russians arrived, liberated the camp, and then went off in pursuit of the Nazis.

15-year-old Eva was one of the few prisoners strong enough to venture outside of the camp.

She made the very dangerous trek to Auschwitz in search of her father and brother.

-And I walked everywhere.

And I came to where another barrack where there was a gray-looking man, standing there, not knowing what to do with himself.

But he looked a bit familiar.

So, I went to him and I said, "I think I know you."

So, he said, "Yes, I'm Otto Frank, Anne's father.

And you are Eva Geiringer."

I said, "Yes."

"So, have you seen my girls or my wife?"

I said, "No, never saw them.

Have you seen Heinz and my father?"

He said, "Yes, but they left with the Germans a few weeks ago."

So, that was good news, really.

And then I went back to fetch my mum.

♪♪ We were dropped at the station, and that was it.

We had no money.

We had nothing, and nobody.

There was no welcoming committee, nothing.

So we stood there and said, "What now?"

You know, it just was terrible, really.

So my mother said, "Well, let's see if this woman, who rented the apartment, if she lets us in again, in there?"

So we went there.

And my mother had the address and she said, "Yeah, it's empty.

You can go.

But, of course, you will have to pay me rent."

So we said, "Yes.

Yeah," but, I mean, we had nothing.

So we went in, and everything was how we had left it.

-The Geiringers' experience, coming home, was very unusual.

Most people, when they returned, did not find their homes in the state they left them in.

Most of their property had been pulsed.

That was a word that was used for the removal of Jewish property from the homes.

-Otto came, as well, to us.

He asked us, "Did you hear anything about my girls?"

He heard that his wife had died.

He knew that then, but nothing about his girls.

So he had hope, and we had hope.

And then, one day, he came and said, "Very bad news.

I've heard that both my girls had died in Bergen-Belsen."

After he left, my mother said, "This man won't be able to live long.

He has given up."

And a few days later, he came again with a little parcel under his arm and said, "I must show you something."

And you can guess what it was.

It was the diary.

And he said, "I must show you, really, an amazing miracle."

And he said, "Can I read you a few lines?"

Which I said, "Sure, of course," and he read it, but he always burst into tears.

It took him -- He couldn't carry on.

It took him three weeks to read it.

First, he couldn't find a publisher, and he wasn't sure he should publish it.

But eventually he published it, and after the war, people didn't really want to know anything -- more horror stories.

So it was not a success.

-There was an attitude in the postwar period, I think, among many people, that, "We're just going to move on and try to survive and see how we can build a new world after this massive destruction."

So, for many people, talking about the war at all was off limits, in a way.

-There was a Jewish journalist from The Times who wrote a wonderful article about it -- that this is a miracle, this book, and it's wonderful and so on and so on.

And that made it immediately a bestseller.

And then, of course, it went from strength to strength, and it hasn't stopped.

Eventually, we got a letter from the Red Cross.

Not a sympathetic letter, just very official, to my mother.

"We have to tell you that your husband, Erich Geiringer," with the birth date, "and your son, Heinz Geiringer," as well with his dates, "perished in Mauthausen," with dates in March.

Some times in March.

And that's it.

That was it.

You know, so...

I, personally, couldn't believe it.

You know?

I didn't accept it.

And I was full of hatred, but really, not just for the Germans, but for mankind in general.

You know?

I just couldn't cope with the world.

And I found, my mother kept it.

I found a little note, which I wrote in January 1946, that, "Life without my father and Heinz is useless.

I really would like to commit suicide."

♪♪ After Otto got the diary, I realized we promised Heinz to get the paintings.

So we were went there and rang the bell, very shaky.

A young couple opens the door.

So, when I told them the story that the paintings there, and there's a floorboard, and so on, they said -- looked at each other, "There's nothing in our house."

Wanted to close the door.

People were still suspicious, you know, of people.

We didn't look particularly nice, you know.

We didn't have proper clothes, or whatever.

-A lot of the Jews who came back experienced that the Dutch people were not interested in their stories.

"We had a harsh time.

There was this fear, uh, famine, and we call it the "Hunger Winter."

♪♪ -But then I started to cry, and my mother said, "Well, let's go, and come back another time."

And I said, "No, no, no.

I must."

And I rang the bell again, and they opened again, and I cried, and my mother started to cry.

And then they looked at each other and said, "Okay, look, but I'm sure there's nothing."

But I knew where it was, so we went up to the loft there.

I knew there was a bit of a space where I could see where, obviously, he had lifted the floorboards there.

And indeed, there was all these books with all the poems, with a note on it that belong to Heinz and Erich Geiringer.

And then, suddenly, all those beautiful paintings.

And that's how I get it.

♪♪ ♪♪ -Otto and Fritzi were married for 27 years until Otto died in 1980.

They devoted themselves to sharing Anne's story with the world.

The diary was turned into a play and a film and translated into many languages.

It saddened Eva that her remarkable brother's story was left untold.

-I was still at school, and I was still terrible miserable.

You can't imagine.

I couldn't sleep.

I had nightmares, and I didn't want... You know, there were -- on the Merwedeplein, there were children were playing again.

And I still didn't want to make friends or anything like that.

♪♪ -He was imprisoned.

He was put in a camp.

But he survived the war.

And he was installed, after the war, again as principal of the Amsterdam Lyceum.

So he continued his work after the war, as well.

-And I finished school.

Otto found a place for me in London for a year to become an apprentice.

But I still didn't talk about my experience.

And I lived here in London, and there was a boarding house where they had some other young people, and one was an Israeli student.

So I became friendly with this Israeli boy.

I didn't tell him that I -- nothing about myself.

Then, after another few weeks, he said to me, "Eva, I've fallen in love with you.

Will you marry me?"

And I said, "No, thank you."

He said, "Why not?"

I said, "Well..." -- and then I told him -- I still didn't tell him, but I said, "I have a widowed mother in Amsterdam.

And once I'm finished with my year, I've got to go back."

But I really wanted to get married.

and I wanted to have children.

That was the only aim I had in life -- "I want children."

And that is because what my father told Heinz -- about that from generation, you live on in generation.

This was one of the reason, as well, why I never gave up, because I said, "If I die, I will be forgotten.

But so I have to survive to get a family, and then I will live on through my children."

So this had made a very big impression on me, I think.

My mother liked the young man.

And then I asked my mother, "Do you think I should marry him?"

And she said, "Yes, I think he's a good man."

So then we went to Amsterdam, because we didn't know anybody in London, and got married there.

[ Soft music plays ] ♪♪ So we were again a family, but I still didn't speak about what had happened to me.

I dreamt always about Auschwitz, about selections, and things like that, and the work we did.

♪♪ -Today is October the 9th, 1996.

The survivor being interviewed is Eva Schloss.

-Of course, I was always afraid of dying.

This was always behind me.

And this was, of course, a terrible part.

And we were always hungry.

As soon as I started talking, I became much calmer and I didn't have nightmares anymore.

♪♪ -Eva wrote three books about her family's experience during the Holocaust and after the war.

Eva has toured Europe, Asia, and the United States as a Holocaust educator.

Her focus now is on the story of her brother and sharing his legacy with the world.

-It became my task that people would remember that who he was and what a wonderful person, what he has achieved, as well, with the poetry.

♪♪ -We have some 17 paintings that were made by Heinz Geiringer, in hiding, between '40 and '43.

We don't know the exact order in which he painted them, but you can see there are a lot of still lifes.

You can see that he's in the process of mastering the art of painting.

He was a teenage boy who I think was very, uh -- very gifted.

I think most of the paintings don't really reflect the experience of being in hiding.

Of course, it's possible sometimes to draw connections.

For instance, here, one of the most striking paintings, I think, Heinz made, of a death mask with an hourglass, which you could easily see as some kind of reflection of killing time, which was what they had to do while in hiding.

What is remarkable, I think, is that these paintings were hidden beneath a floor in the attic, where they stayed for a couple of years.

If you look at them now, they are still very vivid.

The colors are very vivid.

If you compare it to most of the artwork we have that was made in hiding, it's really remarkable.

♪♪ These are the poems that Heinz wrote.

He wrote some of them in German, his mother tongue, but also a lot of them in Dutch, which is really impressive if you imagine that he had been living in the Netherlands only for a couple of years.

-Eva actually grew up in the shadow of Anne Frank, and of course, she and her diary became world-famous.

And it was a little difficult for her because she also had a brother who died and who left all the paintings, but nobody knew them.

So it was very important for her that now people can also see the paintings of Heinz and learn about his story.

♪♪ -Eva's grandson Eric Schloss shares Eva's work, particularly the story of the poet and painter Heinz Geiringer, the great-uncle he never met.

-For her to, over these years, have been able to start sharing his paintings and his poems has been something that, yeah, she's felt like a continuing the remembrance of him and allowing him to have the life that he, you know, obviously didn't have, through his work.

-On an individual level, people did whatever they could to continue their lives until they couldn't continue their lives anymore.

And so creating art or writing in a diary or doing poetry, or anything that made life seem meaningful under these circumstances, was incredibly crucial to -- to a sense of survival.

-Personally, the story is the most important thing that I've promised Heinz -- that he will not be forgotten.

Wherever I speak, this is a very important part of my story now -- telling about my wonderful brother, what a wonderful relationship we had, and how talented he was, how he was going to contribute a lot to the world.

So, Heinz is just one of the victims, but we try not to get more and more victims again, young people dying because we are creating wars and prejudice against people who are different.

People will see who he was.

He will be remembered, and not just as an artist, but as a human being who had big aspirations to make a wonderful life for himself and get a family, and, yes, to live a useful life.

-Heinz Geiringer died at 18.

He never married.

He didn't have children.

His legacy is a collection of beautiful paintings and deeply felt poems.

His memory is kept alive by the stories that his sister and his mother shared with Eva's children and grandchildren.

♪♪ -"Don't cry, Mama.

Mama, do I have to die already?

I heard the doctor say so.

Please, Mama, don't cry.

Heaven is such a beautiful place, and soon we'll be together again.

Mama, what will my little sister say when she wants to play with me again?

Please, Mama, don't cry.

After all, I'll be seeing Dad again.

He's been waiting up there already so long.

Remember to take good care of the kitten.

She loves me so.

Please, Mama, don't cry.

Don't you still love me as much as ever?

Are you still with me?

Please tell me, Mama.

The worst of it is, Mama, that you'll be gone so long.

Please, Mama, don't cry.

For me, to watch you cry is so sad.

Please hold my hands for just a minute.

It seems so misty in the room.

Please, Mama, don't cry.

Mama, just one more thing.

Please kiss me goodbye."

♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ -I'll ask you, Zvi.

Is there anything you would like to say to Eva?

-Yes, uh, I think you've been very strong.

That's how you were able to survive.

And you continue to be very strong and a great tower of strength for everybody.

[ Soft music plays ] ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪

Eva's Promise is presented by your local public television station.

Distributed nationally by American Public Television